From the Southern Ocean to Europe’s Shores: Why collecting ocean data matters

When we think of collecting data to understand our ocean’s health, our minds often go to the deep, wild Southern Ocean; remote, powerful, and largely untouched. But what about the dynamic, busy, and biodiverse European waters? Coastal zones like the ones Team Holcim-PRB sailed through during The Ocean Race Europe 2025 are just as important. In fact, the contrast between the two might be the key to understanding how the ocean and our climate are changing.

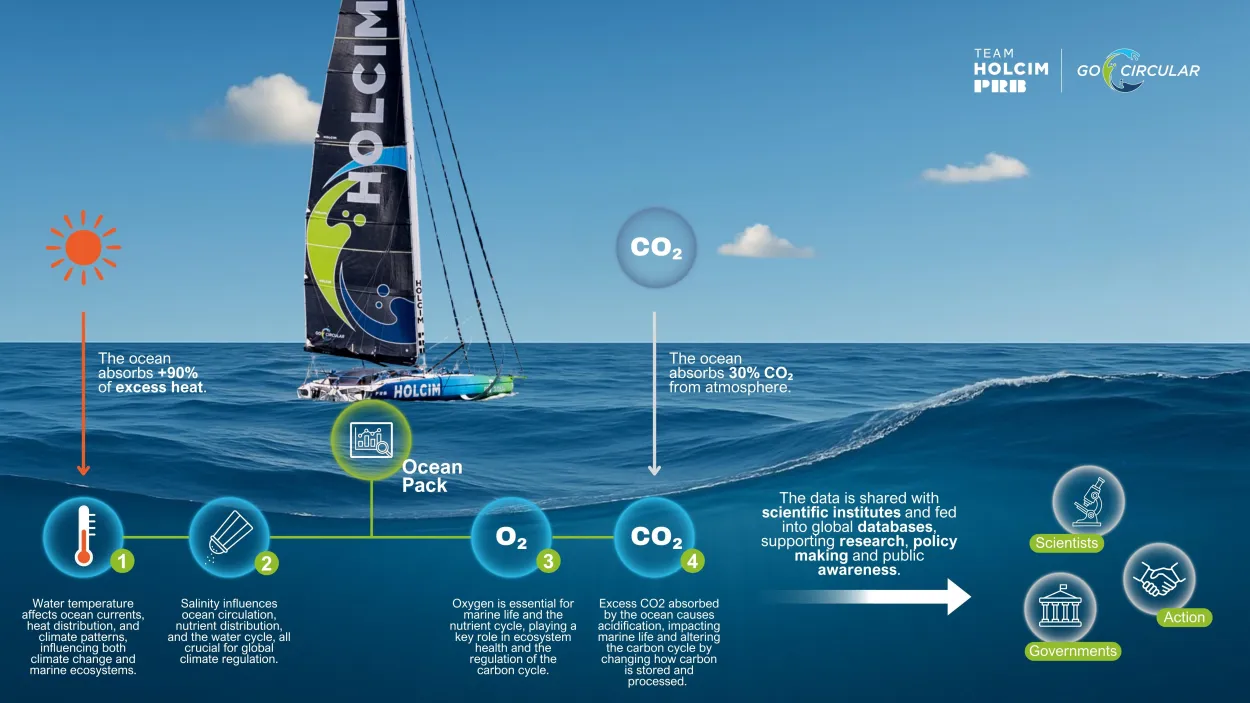

As part of its GO CIRCULAR commitment, Team Holcim-PRB is not only racing from sea to city. It’s collecting valuable oceanographic data via a fully automated OceanPack system installed on board. During the Vendée Globe, Nicolas Lunven gathered nearly 1.8 million data points from some of the most remote waters on earth. Now, in The Ocean race Europe, Team Holcim-PRB again carries the OceanPack onboard, sampling water closer to home. In addition, the team deployed a drifting buoy that moves with the currents to track and study ocean flow. The data captured by these buoys supports global ocean and weather observation systems.

Why Data from All Parts of the World Matter

While the Southern Ocean remains a critical driver of global ocean circulation and carbon uptake, coastal areas are hotspots for biodiversity and climate interaction. Together, they offer a more complete picture of how the ocean functions as our planet’s largest carbon sink.

In coastal zones, there are so many moving parts. You have land runoff, rivers bringing nutrients, human activity, seabed mixing - everything is dynamic. That means we actually need more data in these areas to understand what’s happening. The power of citizen science lies in gathering information and data that help us understand the reality we are currently living in, as well as the possible scenarios we may face in the future.

The combination of many different datasets collected by teams like Team Holcim-PRB offers a more complete picture of how the ocean operates as our planet’s largest carbon sink. Measuring in areas such as the Southern Ocean helps validate carbon budgets and heat distribution models that are essential for predicting global climate behavior.

Each data point collected contributes to a growing global database, helping scientists better understand deoxygenation, acidification, and carbon absorption patterns. These datasets are shared with EMODnet, where scientists use them to inform climate models and decision-making processes.

Boats participating in The Ocean Race Europe are not just racing, they’re crossing multiple marine habitats in a way no stationary instrument can. From underwater canyons to Posidonia meadows.

From the Southern Ocean to the Mediterranean Sea

Team Holcim-PRB is proving that high-performance racing can drive science, education, and change not just in remote oceans, but in the waters we all depend on.

During the Genoa stopover of The Ocean Race Europe, the team joined The Ocean Race, local startup OutBe, and leading data platforms to host a Citizen Science Water Lab. The beachside water lab brought together curious minds of all ages to learn about science, sustainability, and the role of sailing in ocean research, highlighting the importance of raising general awareness and educating people across generations to better understand and protect our ocean. On the beach, visitors explored how sailing contributes to ocean data collection, from measuring CO₂, dissolved oxygen, salinity, and temperature in real time to understanding why European coastal waters are as important to study as the Southern Ocean.

There’s often this idea that we only need to collect data where we don’t have any yet. Yes, remote areas are under-sampled, but you’d be surprised how little we actually know about our own coastal waters. These are areas full of biodiversity, human interaction, and land-sea dynamics, and that’s exactly why we need more data here.

This powerful combination of scientific insight and personal exploration highlighted why understanding the ocean, from surface to seafloor, is not only about numbers, but also about connection.